Innovation Systems

Editor | On 01, Apr 2018

Darrell Mann

‘Successful step-change.’ That’s our usual definition of innovation. Especially if we’re trying to be succinct. ‘Successful realisation of new customer value,’ is the slightly less condensed form. Both represent innovation as an outcome.

And if innovation is an outcome, then the realization of that outcome necessitates the existence of a system. Which in turn means that the Law Of System Completeness must apply. Innovation, in other words, will only be delivered if and when the requisite elements are present:

Figure 1: Law Of System Completeness Applied To ‘Innovation’

Figure 1: Law Of System Completeness Applied To ‘Innovation’

We mention this because it seems there is still considerable confusion as to the relationship between various different elements that managers and leaders have connected to the ‘innovation’ word. Not least of which being the word ‘design’. Everyone these days, it seems, needs to get involved in ‘Design Thinking’.

Well, according to Figure 1, that’s absolutely right. Everyone does need to get involved in ‘design’ if the seek to achieve successful step-change, or ‘new customer value’. ‘Design’ in the context of the Law Of System Completeness is the process by which the ‘technology’ is transformed into the eventual Innovation Solution. It is a necessary, but fundamentally insufficient aspect of new customer value.

This ‘insufficiency’ seems to be confusing to what feels like a majority of organisations that have embarked upon – usually expensive – ‘Design Thinking’ education programs. Great that they’ve been through the journey. Not so great that they were promised tangible outcomes that never arrived.

We can see a similar ‘necessary but not sufficient’ misunderstanding in many other organisations who embark on equally expensive ‘technology development’ programs. Specifically, Innovation Capability Maturity Model (ICMM) Level 2 organisations, who are in my ways characterized by their terrific ability to do R&D that results in elegant technological solutions that get to sit on a shelf waiting in vain for an opportunity to be picked up by a commercialization project team. We’re using the term ‘technology’ in its broadest possible meaning here. ‘New technology’ could be a new algorithm as much as it could be a novel turbine blade material, as much as it can be the discovery of a better way to understand why customers tell us one thing and then behave in a completely different manner. ‘Technology’ in this broad sense is the ‘Engine’ of an Innovation system. It is the new knowledge that enables innovation to happen, but by itself, it is fundamentally no innovation.

Recently, we’ve taken to drawing this ‘necessary but not sufficient’ Innovation System story as a two-part Venn diagram. The first part is intended to try and overcome the confusion between ‘technology’, ‘design’ and ‘innovation’:

Figure 2: Innovation As A (Venn Diagram) System – Part 1: ‘Core’ Â

Figure 2: Innovation As A (Venn Diagram) System – Part 1: ‘Core’ Â

The first thing to notice about this picture is that we’ve added ‘Anthropology/Psychology’ to the Design, Technology, Innovation triad. Our ability or otherwise to understand the needs of customers (‘Market Demand’) is as fundamental at the core of any innovation activity. The ‘Design Thinking’ has in many ways try to subsume this kind of anthropology activity into how the ‘design process’ operates. The problem with that attempted absorption is that the Design Thinking world is much better at design processes than it is at understanding how and why customers behave in the way that they do. Dig into the guts of any Design Thinking curriculum, in other words, and you’ll quickly begin to realise that their version of ‘understand the customer’ pretty much boils down to ‘empathise with them, then get a prototype in their hands as quickly as possible so you can iterate as quickly as you can to a better solution’. Which isn’t a methodology at all, it’s merely a transmission process. If it was a methodology, it would contain some or all of the tools in our TrenDNA toolkit, and everyone would save themselves an awful lot of wasted time presenting customers with random ideas.

Second up, the idea behind the Venn Diagram analogy is to recognize several things:

- that it’s perfectly possible for an ‘innovation project’ to exist in any segment of the Diagram so long as I don’t expect it to deliver the desired ‘new customer value’ outcome. The point is to know which segment we’re in, so that we know which ones we need to go to after we’ve finished our bit in order to get to the next bit.

- The relative amount of each of the four elements in any given innovation project will very likely change. Many projects, for example, will pay very little attention to ‘new technology’ at least in the traditional sense. Whenever we create a new PanSensic lens, for example, we barely recognize that algorithm as a piece of technology at all, and it will usually feel like the ‘easy’ part of the overall process of turning it into ‘new customer value’. Conversely, putting Man on Mars will likely require an awful lot of ‘technology’ and not so much Anthropological study of ‘Market Demand’. Just so long as we remember before we finish, that we need to have spent some time and energy in each of the four elements of the Diagram.

- Although a ‘typical’ innovation project will tend to evolve from left to right across the Diagram – i.e. understand the customer and the technology before translating it into the Innovation – the temporal sequence of each of the four activities will also likely change from project to project. Some projects will start with a new piece of technology; others with a desire to keep a Design team active. Again, the ultimate point being that so long as we end up having ‘done’ all four segments, it doesn’t particularly matter what order we do them in. In many ways, the ‘Design’ (Transmission) process is the thing that can help to guide the way.

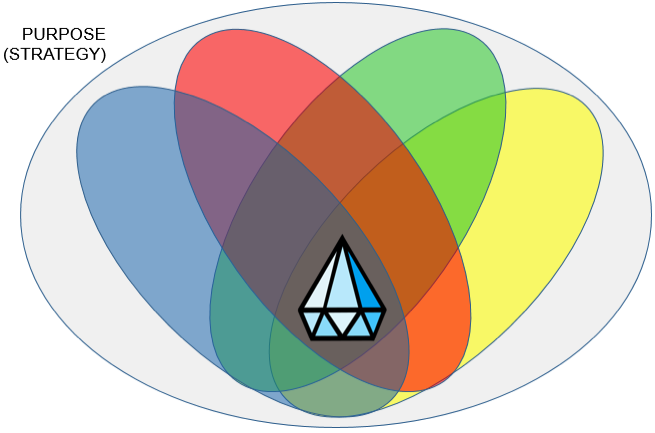

Figure 2 still leaves us with two pieces missing from our ‘Complete System’ Law. Do the Anthropology, Technology, Design and Innovation jobs and we still won’t achieve ‘new customer value’. That’s only going to happen when we integrate these four elements into a higher level ‘Coordination’ story, we typically call ‘purpose’ or, more pragmatically, ‘strategy – Figure 3:

Figure 3: Innovation As A (Venn Diagram) System – Part 2: ‘Super-System’Â

Figure 3: Innovation As A (Venn Diagram) System – Part 2: ‘Super-System’Â

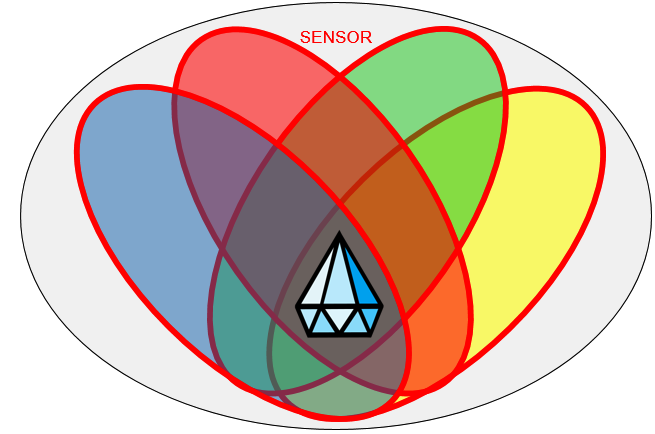

Finally, more difficult to draw than the other five elements is the sixth ‘Sensor’ part of the system. It’s not possible to achieve ‘new customer value’ (the diamond in the centre of the Figure 3 image) if we’re unable to measure all the things that are happening. The ‘Sensor’ part of the system sits between the overall Coordination and the other four elements, and as such it often gets absorbed into the ‘Coordination’ element. The further we get ourselves into the PanSensic story – a business that is completely about creating and delivering ‘sensors’ – the more we see how dangerous it can be to make this element invisible. Most innovation (‘new customer value’) attempts fail, we now know, because the requisite measurement elements are not in place. Figure 3 very likely makes us guilty of the same invisibility error. Which doesn’t make drawing the right picture any easier. Figure 4 is the best we’ve achieved so far – the sixth ‘Sensor’ element becoming the element that sits at the interfaces of the other five elements:

Figure 4: Innovation As A (Venn Diagram) System – Part 3: The Essential Sixth Element

Figure 4: Innovation As A (Venn Diagram) System – Part 3: The Essential Sixth Element

The thing about the Law Of System Completeness is that it’s a Law. If we have a desire to deliver a useful outcome, we know we need to abide by the rule of Law…

…something we’ll see again in the article Equality (Or Not)

…something we’ll see again in the article Equality (Or Not)