Design for Wow 3 – Literature

Editor | On 27, Aug 2006

Darrell Mann

Systematic Innovation Ltd, UK.

Phone: +44 (1275) 337500, Fax: +44 (1275) 337509

E-mail: darrell.mann@systematic-innovation.com

www.systematic-innovation.com

Melissa Mann

Writer

Phone: +44 (7985) 192052

E-mail: info@melissamann.com

www.melissamann.com

Introduction

This article is the third in a series, which aims to explore the ‘wow’ phenomenon in different subject areas. The first article (Reference 1) looked at ‘wow’ in general, while the second (Reference 2) shifted to the more specific area of music. In this one, literature is the focus of study. This preliminary research set out to identify memorable books or moments in books with a view to understanding what patterns or principles, if any, make these wow moments stick in people’s minds more than others.

Our methodology is explained, the resultant findings laid out, key conclusions presented and recommendations for taking this study further are made.

Initial thinking and methodology

We recognised before embarking on this study that emotional context would play an important role in determining people’s wow moments in literature, and potentially much more so than was found to be the case in music. A reader may experience an emotional wow with a book because it “speaks†to them in some way. For example, it may strike a chord with how they felt in a similar situation. This certain something may speak to them only in that moment, i.e. is linked to their mindset at the time they were reading the book, or it may be more enduring. The same book without this personal, emotive context may have no impact at all on another reader. In addition, it may not always be clear why a book or a moment in a book “speaks†to the reader. Perhaps it taps into something personal in their subconscious mind or more likely, it creates in the reader a strong empathy for the character and the situation confronting them. The reader’s emotions may be stirred by the humanity in a piece of writing and as a result, they feel for or even feel with the character.

Of course, achieving this emotive state is at the heart of good fiction writing. Creative writing courses teach the principle of the fictive dream, which the writer creates by the power of suggestion and which takes the reader to a state of altered consciousness. This fictive dream state is achieved by the writer using vivid detail to involve the reader emotionally with the characters and their plight. This involvement arises from the writer gaining the reader’s sympathy, getting them to identify with the character and most important of all, ensuring the reader empathises with the character to feel what they are feeling.

We also thought that the way people read books would have an impact on the study. Unlike music where the listener returns to an album or track time and again, books or chapters in books tend not to be frequently re-read. Furthermore, people read in different ways and for different reasons. Some speed read, as a means of preparing for sleep for example, and are happy just to get the gist of the story. Other readers however, are more committed, devoting time and concentration to taking in and understanding every word. Memory therefore can play a role in a person’s ability to recall with precision a book or moment in a book they felt had the wow factor, quite apart from being able to define why it had this effect on them.

Bearing these factors in mind, we concluded that drawing data from a large number of people would be key to the robustness of the research. This study then should be seen as just the start of a much wider piece of research. Let us begin by explaining the primary research that forms the basis of the work carried out so far. Over twenty-five people contributed to the research carried out largely by e-mail during the period September to December 2005. Participants were asked two basic questions:

• what books or moments in books (e.g. a chapter, scene, paragraph or it might even be just a sentence or a word) are particularly memorable for you or to use a buzz phrase, create an emotional WOW for you?

• what is it about the book or moment in the book that makes it so memorable or creates that WOW effect?

The following section is a collation of the findings of this research.

The research findings

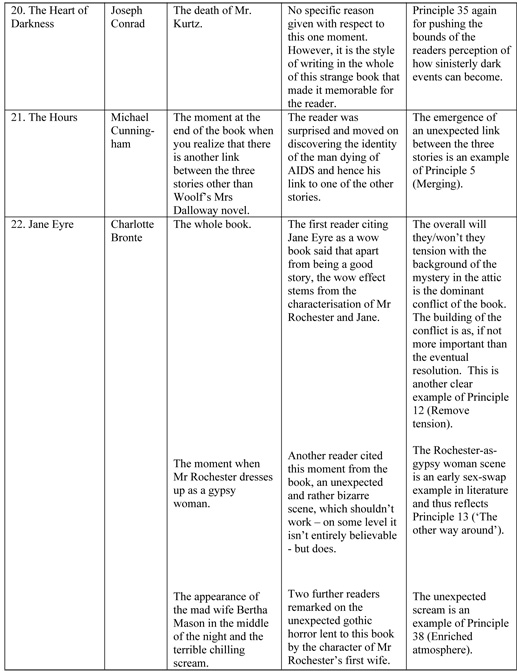

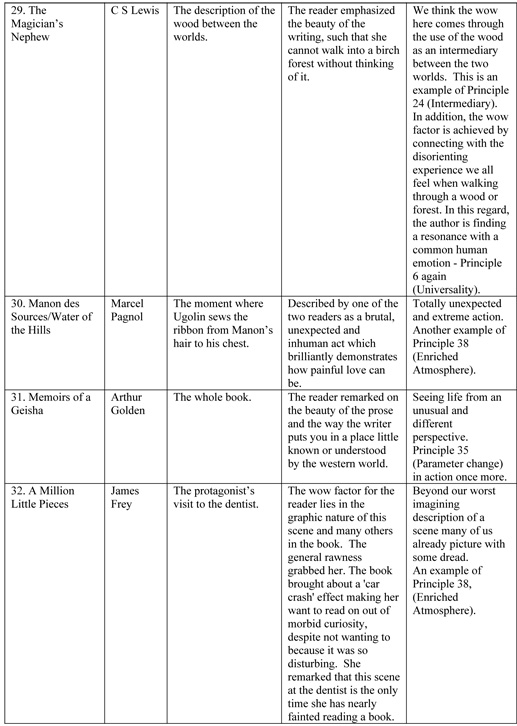

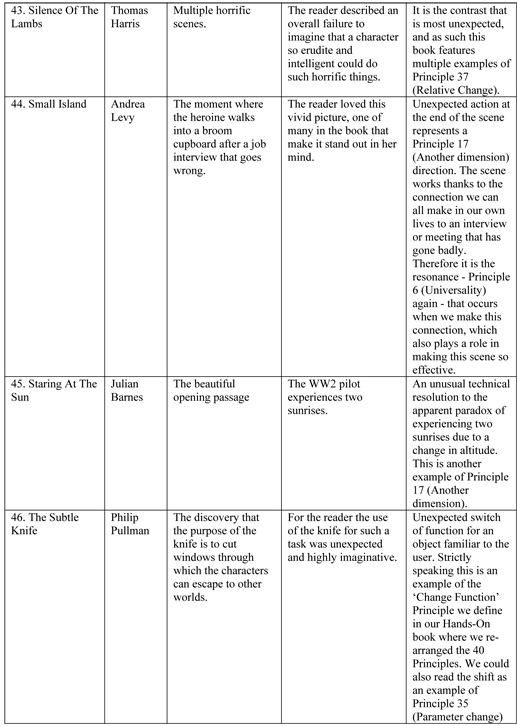

The table below identifies the title and author of the book, any specific moments identified as being memorable and the reason why the book or moment in the book was memorable for the reader, if specified. The table is in alphabetical order by title.

Some Theory

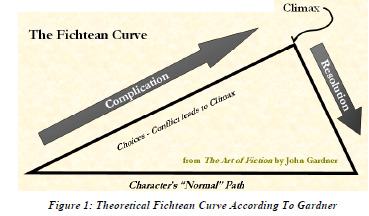

In a parallel article to this one (Reference 3), we discuss the idea that there are only a relatively small number of possible literary plots. What this Reference 3 article tries to demonstrate is that although there are a finite and manageable number of different plots, the literary community’s assessment that there are variously one-plot, three, seven, 20, 36 or 37 plots (Reference 4), is both naïve and incomplete. The ‘only one plot’ story, however, is an interesting one, and indeed is potentially very important to the ‘wow’ research conducted for this article. Among the ‘one-plot’ perspective holders are people like E.M.Forster, William Foster-Harris (Reference 5) and, perhaps most significantly, John Gardner (Reference 6). All three come to the conclusion that all literature is about the emergence and resolution of a conflict. While this might not strike us immediately as a ‘plot’ as such, it is quite significant from a TRIZ perspective. Gardner talks in the most detail about the significance of conflict resolution. In particular he introduces the idea of the Fichtean Curve. Figure 1 reproduces this curve. Regular readers may recognize elements of this picture in our previous discussions on the basis of what evokes a ‘wow’ reaction in people when they hear a joke or see a piece of great design or hear a great piece of music (Reference 1, 2 respectively) – that is, someone expects one thing (the ‘normal’ path) which turns out to be different from the place the designer or composer or joke-teller takes them. Then, when the conflict is resolved – after a ‘climax’ to use the expression found in the Fichtean Curve figure – that is when the ‘wow’ moment is experienced.

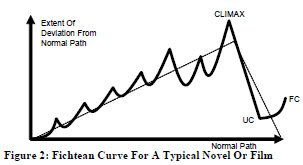

We can (and ought to) take this point further by picking out another aspect of this curve described by Gardner: The Fichtean Curve shown in Figure 1 represents the basic ‘plot’ of a book. In reality, however, authors or screenplay writers often introduce a multitude of conflicts. Whether consciously or not, what writers are doing when they do this is trying to increase the curiosity of the reader or viewer. As an audience, we appear to be naturally drawn to surprising and unexpected things. This probably goes a long way to explain why it has been possible to correlate ‘wow’ and conflict resolution in other disciplines. We appear to be inherently drawn to things that are not as we expect them to be. Figure 2 illustrates how writers frequently exploit this tendency.

What we observe here is the use of multiple mini-conflicts. The function of these miniconflicts is to keep the reader interested throughout the book. Whether you are a fan or not, the current book phenomenon that is Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code represents a great example of this plot device in action. In the book, the main character is forced to find and resolve a series of mini-conflict clues in order to make progress towards an ultimate prize. Also worth noting in Figure 2 are the UC and FC points. While these aren’t always present, they do reflect common archetypes that are consistent with the overall Fichtean Curve premise. ‘UC’ can be thought of as the unfinished conflict resolution. We see this in many films and books in the 1970s and 80s where the denouement only partially resolves the main conflict. As readers or viewers we experience this unfinished resolution as a doubt. The unfinished conflict may thus be viewed as a device to keep the reader thinking about the book after they have put it down, and ideally to have any ‘wow’ effect continue after the book has been returned to the book shelf. FC, on the other hand is a device to set up the premise for a sequel and used to great effect primarily by the film industry. FC is a mini final-conflict that is introduced after the denouement and then deliberately left unresolved: did the baddy really die? Did the monster leave behind the seeds of another? And so on.

Analysis Of Literature Study Results

In all, the survey identified and described ‘wows’ from 63 different books. Some of the books were selected by multiple readers, occasionally for different reasons. Where ‘wows’ were repeated by multiple readers, we have only included them once in our analysis. Where readers identified different ‘wows’ within the same book, we have included those as separate entries in our analysis. In all the analysis contains 81 wow examples.

One of the first things we can say about the results of the survey presented in Table 1 is that in every case it has been possible to make a clear connection between the ‘wow’ experienced by the reader and some kind of a conflict. We may also see a number of similarities with the results of our findings from the analysis of wow in music (Reference 2). First and foremost, and a good place to start is an observation that the ‘wow’s occur at three distinct levels: some at what we might describe in TRIZ as the ‘system level’ – i.e. the wow emerged from the overall plot or story-line – some at a higher ‘super-system’ level – i.e. an invention related to the genre or structure of book – and some (the largest number in fact) at the ‘sub-system’ level. These sub-system level ‘wows’ varied in size and scope from an individual phrase (‘starless and bible-black’) to particularly effective sentences to longer passages. The breakdown between these three different levels is as follows:

Looking more closely at the 81 different wow’s, we can observe that all can be clearly correlated to the existing 40 Inventive Principles found in TRIZ. In descending order of frequency, the Principles observed were as follows:

• 15 Examples – Principle 35 (Parameter change)

• 12 Examples – Principle 13 (‘The other way around’)

• 6 Examples – Principles 5 (Merging), 17 (Another dimension), 18 Resonance), 37 (Relative change)

• 5 Examples – Principles 7 (‘Nesting’), 38 (Enriched atmosphere)

• 4 Examples – Principle 6 (Universality), 12 (Remove tension)

• 3 Examples – Principle 10 (Prior action)

• 2 Examples – Principle 20 (Continuity of a useful action)

• 1 Example – Principles 2 (Taking out), 3 (Local quality), 8 (Counterweight), 24 (Intermediary), 26 (Copying), 28 ((Another sense), 40 (Composite structures)

Thus, in all, we were able to identify examples of 19 of the 40 different Principles. Of course, the small sample size makes it impossible to say anything meaningful about the relevance or otherwise of the other 21 Principles. Likewise it is difficult to comment meaningfully on the frequency with which the 19 identified Principles are used. Looking at the most frequently used Principles – 35 (Parameter change) and 13 (The other way around) – we can, however, say that there is a strong correlation here between what has been observed in our analysis of wow in literature and what has been seen elsewhere: Namely, on average, these two Principles are consistently in the Top 5 most commonly used conflict resolvers across all other analysed disciplines (e.g. Reference 7, 8). We can now add literature on the basis of the findings of this study.

The relatively high frequency of Principle 18 (Resonance) examples is due to the fact that we chose not to exclude ‘wow’s that occurred because of a particular and personal resonance between a writer, the characters and situations they create and a given individual reader. This represents a change from the strategy we applied in earlier analyses. We made the change in part because of the smaller sample size, in part due to our inability to get different readers to review and discuss the findings of other readers (something we had been able to do in our analysis of wow in music), but mainly because we think there is something different about wow’s in literature compared to other media as we set out in the initial thinking section at the start of this article.

Although the survey has clearly demonstrated the potent link between ‘wow’ and conflict, one thing we notice that is different between ‘wow’ in literature and wow in other fields is that it is frequently the case (in around 12 of the 63 presented examples) that it is the conflict itself rather than the resolution of the conflict that creates the ‘wow’ effect. A classic example of this is Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice. Although difficult to generalize totally, the enduring attraction of the book seems to be far more closely linked to the ‘will-they-won’t they’ tension between the two main characters as it does from the actual resolution and denouement. It is not the resolution or even method of resolving the conflict that creates the wow – they end up together after Elizabeth realizes she has misunderstood Darcy’s actions; big deal – but rather the fact that the tension caused by the conflict is maintained (and indeed intensifies) over the course of the novel. This ‘wow comes from the conflict itself’ feature is something we will no doubt be looking for in other media from now on.

Conclusions

As in other media, we have shown there to be a very strong correlation between conflict and conflict resolution and the creation of a ‘wow’ effect. Every one of our 63 examples fits the model. Likewise every one of the 81 conflict resolution examples also fit the existing TRIZ Inventive Principle structure. This is not to say that for literature to succeed in being memorable to readers, it requires the presence or resolution of a conflict. However, all the signs point to the idea that both play a vital role.

The question now remains whether we can (or ought!) to turn these analytical findings around the other way and begin to apply them pro-actively in the creation of new literature. It is often said that the easiest way to kill peoples’ enjoyment of something is to analyse it and therefore ‘take the mystery out of it’. Alas, whether we like it or not, someone sooner or later will inevitably do the job. In References 4 through 6 and then Reference 9 we can see that there have already been several attempts at creating prescriptive ‘here’s how to write a best-selling book’ guides. Rather than seeing such an act as destructive, however, the reason why the analysis happens – and why we have done it here – is that it ultimately comes to open the door to new ways of thinking. It is our hope that such a seed has been planted in what we have presented here in this article.

References

1) Mann, D.L., ‘Design for Wow: An Exciter Hypothesis’, TRIZ Journal, October 2002.

2) Mann, D.L., Bradshaw, C., ‘Design For Wow 2 – Music’, TRIZ Journal, October 2005.

3) Systematic Innovation e-zine, ‘The 36 Literary Plots and Their Relationship to TRIZ’, Issue 48, March 2006.

4) Internet Public Library, University of Michigan, http://www.ipl.org/div/farq/plotFARQ.html

5) Foster-Harris, W., ‘The Basic Patterns of Plot’, University of Oklahoma Press, 1959.

6) Gardner, J., ‘The Art Of Fiction’, Vintage Books, 1983.

7) Mann, D.L., ‘Hands-On Systematic Innovation For Business & Management’, IFR Press, September 2004.

8) Mann, D.L., Dewulf, S., Zlotin, B., Zusman, A., ‘Matrix 2003: Updating the TRIZ Contradiction Matrix’, CREAX Press, 2003.

9) Epel, N., ‘The Observation Deck: A Toolkit for Writers’, Chronicle Books, 1998