Crowdsourced and crowdfunded business models viewed as complete (technical) systems

Timothy Brewer | On 01, Dec 2015

Published previously in TRIZ Future 2013

Timothy Brewera, Ellen Dombb, Joe Millerc, Darrell Mannd

aTimothy Brewer Design, 1740 Raymond Hill Road, #3, South Pasadena, CA 91030, USA

bPQR Group, 190 N. Mountain Ave., Upland CA 91786 USA

cPQR Group, 190 N. Mountain Ave., Upland CA 91786 USA

dSystematic Innovation, 5a, Yeo-Bank Business Park, Kenn Road, Clevedon, BS21 6UW, UK

Â

Abstract

Crowdsourcing of conception, design, and development of products and services and crowdfunding of business startups and a variety of methods of launching new businesses that differ dramatically from the past have emerged in the last 5 years. Â New systems such as Quirky and Edison Nation and Threadless provide inventors with a pathway to new business without the risk of learning and capitalizing such skills as supply chain management, manufacturing, distribution, and marketing. Â Funding platforms such as Kickstarter in the US and Pozible in Australia, Camp-Fire in Japan, and many others liberate entrepreneurs from the need to raise money by selling equity interests or by taking on debt, and simultaneously provide market research, since the popularity of the idea can be judged by the response of the community of potential contributors.

Previous research has demonstrated the usefulness of the TRIZ system of complete (technical) system analysis to increase understanding and effectiveness of managing new business models based on inclusion of social responsibility in the definition of business success,  [1] as well as the traditional application to product improvement. Application of the classical 5 element model and the enhanced 6 element model to the crowdsourcing and crowdfunding new business models will demonstrate both the effectiveness of the TRIZ analysis and the most probable future expansion of the crowdsourced and crowdfunded business systems.

© 2013 Published by Elsevier Selection and peer-reviewed under responsibility of ETRIA.

Keywords: Â TRIZ, Complete Technical System, TRIZ for business models, Crowdfund, Crowdsource, Kickstarter, Quirky

1. Introduction

TRIZ has been applied in the last 20 years to business situations and business models with great success, helping researchers to develop new insights into the business. [2] [3] More recently TRIZ has been applied to new definitions of business that include social responsibility and global impact as well as traditional business success measures such as sales and profits. The analysis system of the 5 elements of the complete technical system has proven particularly helpful. [1] These studies addressed the on-going, operating phase of the business lifecycle, but did not examine the start-up phase, which has historically been the highest failure stage of business life. Taking a lesson from earlier work on the importance of time-dependent function modeling [4] this work applies both the 5 element method and the new 6 element approach developed by Mann [5] to the startup phase of new business models which are now emerging. These new business models radically change the risk of new business creation by changing the patterns of involvement and commitment of capital and creativity. [6] Here, we define “risk†as the exposure of intellectual property, financial resources, labor, time, reputation, etc., to potential loss.

“Crowdsourcing†is the term used for participation of outsiders (not employees or contractors to a company) in the design and development of a product, service, or system. The outsiders can be customers or potential customers, or members of communities of interest, which are usually (but not necessarily) Internet based. “Crowdfunding†is the term used for raising money without offering conventional debt or equity, from the same kind of “crowd†of outsiders.  In some implementations both crowdsourcing and crowdfunding are used, and in others they are separated.

1.1 Complete (technical) system

To improve a system, the TRIZ practioner uses a sequence of questions and answers.  For example:

Is this a complete system?

If “no,†provide the missing elements.

If “yes,†decide how to improve:

Either improve the weakest elements of the system

OR eliminate the system by transitioning the functions of that system to the supersystem

The decision is based on the maturity of the system, the maturity of the system elements, and the ability of the supersystem to support the needed functions.

The TRIZ tool that has historically been known as the 5 elements of the complete technical system can be traced to the Seventy-six Standard Solutions, where solution 1.1.1 says that if a system is not functioning, or not functioning properly, look to see if one of the 5 elements is missing or damaged. [7] Table 1 lists the 5 elements, with definitions, for a simple mechanical system (hammer moves nail) and a simple human system (instructor educates student.) [8] [9] We propose dropping the word “technical†from the name of this tool, since it is extremely useful in non-technical systems analysis as well.

Table 1. The 5 elements of the classical complete (technical) system

| Element | Description | Function 1: The hammer moves the nail. | Function 2: The instructor educates the student. |

| Tool | Performs the function on the object | Hammer | Instructor |

| Energy | Makes it possible for the tool to do work | Human muscle power | Human |

| Transmission | Delivers the energy to the tool | Hand gripping handle | Voice |

| Guidance and control | Adjusts and improves the function (active) or enables the function (passive) | Human eye/hand/brain | Questions, answers, and observation of student behavior (attention, body language, etc.) |

| Object | The thing that is changed as a result of the function (or, The thing that has some attribute changed as a result of the function) | Nail | Student |

The 6 element system proposed by Mann divides the Guidance and Control element into two parts, the sensor and the feedback system. [6] The purpose of this division is to help the researcher on understanding 3 things:

- How information on system performance is collected or “sensedâ€â€”this could be the attributes of the object, the operation of the transmission or the engine, etc.

- How the information is processed.

- How the results of that processed information are fed back to control the operation of the system.

We will use the 6 element model because of the added clarity it offers.

Fig 2. The 6 element model of the complete (technical) system. Top: Business applications. Bottom: General situations

1.2Â Crowdsourcing case study: Quirky (quirky.com)

See [10] for an extensive review of the business models for Quirky [11] and an analysis using the TRIZ system operator. Briefly, inventors submit ideas through the Quirky system. Members of the crowd and members of the Quirky professional staff evaluate the ideas and send feedback to the inventor. A small proportion of the ideas are selected for development, through several stages of improvement (with improvement ideas from both crowd and professional staff.) Surviving ideas are then converted into designs, manufactured, and sold, using direct sales, retail distribution, and sales to social networks of the crowd members. The profits from the product are divided between Quirky, the inventor, and the crowd members who contributed to various phases of improvement. All three groups are rewarded:

- The inventor gets the services of an experienced design, development, production, distribution, marketing and sales company, so he/she sees the idea developed much faster and with much less risk than would have happened in conventional business, where fundraising, product development, distribution and marketing would have been required.

- Quirky gets a continual flow of new ideas, and high confidence of marketability of ideas that are accepted.

- Crowd members get the satisfaction of seeing their contributions implemented, having products that they want made available, and financial rewards for their contributions. Crowd members also may build their own experience and reputation within the Quirky community by means of very low risk participation.

1.3 Crowdfunding case study: Kickstarter (kickstarter.com)

Crowdfunding as practiced in 2013 began about 10 years ago, primarily as a way to solicit funds for charities. Â Crowdfunding raised US$ 3 billion for a wide variety of enterprises in 2012, an increase of 91% over 2011. Â Kickstarter, founded in 2009, is the largest and most diverse of the many organizations now identifying themselves as crowdfunding platforms, hosting funding campaigns for artistic endeavors, product development, and charitable causes. [12] [13] Kickstarter will be the primary case study example for the application of the complete (technical) system model to crowdfunding. A brief overview of the Kickstarter version of the crowdfunding process is as follows:

- An entrepreneur has an idea, and submits it to Kickstarter.

- The Kickstarter staff screens several thousand ideas a week, and selects a small number for posting on its site (the opacity of the selection process has been the impetus for variations on this model used by some competitors like Indiegogo.)

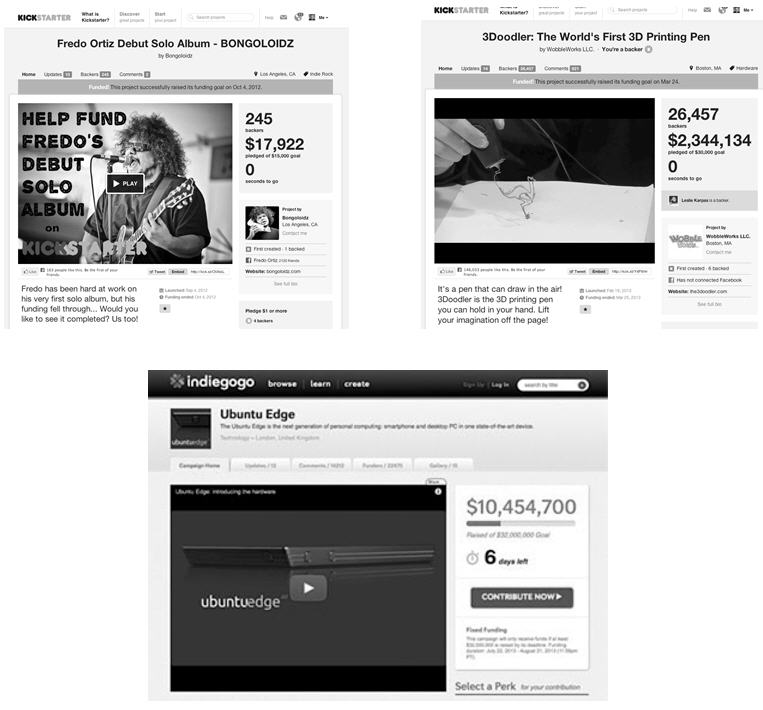

- In a typical posting, the entrepreneur asks for money to do something. In the examples shown in Figure 3, one is asking for US$15,000 to produce a music release, another is asking for US$30,000 to finish development of the 3Doodler, a 3D drawing system, and one is asking for US$32,000,000 to develop and produce the Ubuntu Edge, a replacement for both smartphones and PCs.

The entrepreneur lists rewards for backers (this step is skipped for charitable fundraising.)  For the music release, contributors at the $500 level will get a private music lesson from the entrepreneur, as well as the tee-shirt, DVD, and downloads given to lower level contributors.   For the 3D drawing system, contributors above the $70 level will get early releases of the product, and higher-level contributors will get the early release plus more products and supplies later. For the Ubuntu Edge, contributors above $675 will get units, corporate contributors will get systems of units, and all contributors will influence the future developments.  The founder has said, “This first version of the Edge is to prove the concept of crowdsourcing ideas for innovation, backed by crowdfunding. If it gets greenlighted, then I think we’ll have an annual process by which the previous generation backers get to vote on the spec for the next generation of Edge.†(http://m.techcrunch.com/2013/07/25/if-the-ubuntu-edge-crowdfunding-experiment-works-backers-may-get-to-vote-on-specs-for-the-next-model/) The first two are Kickstarter projects and the third is an Indiegogo project.

- Kickstarter posts the campaign, with a time limit assigned to the fundraising.

- Pledged contributions are held in typical e-commerce style, (credit card, PayPal, etc.) with a time delay. If the campaign does not reach its goal within the time limit, the money is not collected.   This is a significant difference from conventional business—the entrepreneurs either get the money they need, or they get nothing, so the pledged contributors are somewhat protected from situations where the entrepreneurs don’t have enough money for the work needed. Another significant difference is that the entrepreneurs get a substantial amount of market research and validation, since they find out if enough people are willing to pay to participate in the venture.

- If the contributors offer more than the entrepreneurs asked for, the entrepreneurs keep the money (presumably to use to develop more products or to improve the one they offered, but there are no limitations.) In the 2 examples shown, the musician who asked for $15,000 raised $18,000, and the 3D drawing system developers who asked for $30,000 raised more than $2,300,000, making headlines in the business press. [14] Clearly this also differs dramatically from conventional business, where entrepreneurs typically have to give up equity in their company to their investors, or they have to reject the funds. In the Kickstarter model, a popular idea rewards both the entrepreneur and the backer.

Fig 3. (Top, Left) Campaign to raise $15,000 to complete a music production. (Top, Right) Campaign to raise $30,000 for production development of a 3D drawing system. (Bottom) Campaign to raise $32,000,000 to produce a high-end smartphone. [15]

In business functions, the money may be the energy in the system, or it can be the sensor system, or occasionally it can operate as any of the 6 elements. The examples will show how the 6 elements can be used to understand the crowdsourcing and crowdfunding models (Quirky and Kickstarter) in comparison to conventional business operations.

2.1 Complete (technical) system analysis of a crowdsourcing example: Quirky

Table 2 compares conventional business with the Quirky model that reduces the inventor’s risk multiple ways: the crowd submits ideas for new products and provides feedback on the ideas in the initial development stages. As the idea moves toward production—the crowd contributes ideas about the name, packaging, colors, materials, finishes, and the price as well as the functions and features of the product. The Quirky professional staff reduces the inventor’s risk by using an established product development processes and a group of suppliers/subcontractors for protection of IP, manufacturing, distribution, and sales, which are elements that inventors typically have to either learn on their own or hire others to do for them

Table 2. Comparison of the 6 elements for Quirky and conventional business, for the function of product concept generation

| Conventional Business | Quirky | |

| Tool | Internally Generated Idea | Externally Generated Idea |

| Object | Product | Product |

| Energy/Engine | Persuasion | Persuasion |

| Transmission | Communication | Communication |

| Sensor | Internal Human opinion | External Human opinion |

| Control | Management | Community + Quirky staff |

Table 3 shows a comparison for the stage of development where the idea is transformed from a concept or prototype to a manufactured product. This includes many processes, such as design, engineering, verification and validation, tooling, finding or building a fabrication facility, developing quality assurance methods, etc., for a physical product (and for its packaging and delivery system,) and design, development, validation and test, etc., for a software product (and for its delivery system as well.) For this analysis we have grouped these processes into the “product creation†stage.

Table 3. Â Comparison of the 6 elements for Quirky and conventional business, for the product definition and creation stage.

| Conventional Business | Quirky | |

| Tool | Entrepreneurial company | Inventor |

| Object |  “Design†|  “Design†|

| Energy/Engine | Entrepreneurial company resources | Quirky resources |

| Transmission | Infrastructure developed by entrepreneurial company OR infrastructure of a product development and manufacturing company. | Quirky infrastructure (staff and subcontractors) |

| Sensor | Development process reports Project Management, Design Reviews, “Earned Valueâ€, Market Testing, etc | Frequent (Almost Real Time) reports on development progress |

| Control | Modifications (if resources permit). Schedules,  Design Review, Design Freeze, BUDGET, Cost Accounting | Modification of design to improve producibility “Open†receipt of on-going suggestions from “Crowd†|

“Design†in table 3 is broadly defined including concept, specification, and identification of provision process

The table makes it clear that the advantage to the inventor of working with Quirky is that the product gets to market fast, and the inventor does not have to become an entrepreneur, acquiring resources and knowledge of design, engineering, production, distribution, etc. The inventor also avoids the risks associated with either performing or paying other for all these functions. The disadvantage, of course, is that the inventor gives up control of the product, and shares the profits with Quirky and the crowd contributors.

2.2 Complete (technical) system analysis of a crowdfunding example: Kickstarter

Table 4 shows a summary comparison of the 6 elements for the Kickstarter case study and for conventional business for the function of early-stage funding. For conventional business, this is the point where the idea is developed well enough, and a business plan is developed to bring the idea to market, so that the entrepreneur can present the idea and the business plan to funding sources, which could range from angel investors to friends and family, venture capital funds, banks, or other sources. For the Kickstarter-type crowdfunding model, this is the point where the initial crowd opinion plus the crowdfunding platform staff opinions have resulted in the decision to post the challenge.

Table 4.  Comparison of the 6 elements for crowdfunding (Kickstarter/Indiegogo, etc.)  and conventional business for the function of obtaining early-stage funding. The Ubuntu Edge example is at this stage.

| Conventional Business | Crowdfunding | |

| Tool | Entrepreneur | Entrepreneur |

| Object | Funding source , $$$$ | Backers (Kickstarter contributors) , $$$$ |

| Energy/Engine | Persuasion, Business plan plus promise of return on investment | Persuasion, product idea, specific rewards |

| Transmission | Presentation of the Opportunity and plan | Presentation of idea, usually short video |

| Sensor | Response is yes/no, plus entrepreneur’s impressions of the interview | Money pledged by backers, data on how many contributors and amounts. Rate of Pledge Accumulation. Also ideas contributed by backers. |

| Control | Entrepreneur may make changes, but is doing this without much input, or with contradictory input from multiple interviews | Entrepreneur can modify the idea if contributions don’t meet the challenge level.   Goal, time to reach. |

The conventional method requires much more lead time and usually requires the entrepreneur to invest considerable money in preparation of the business plan, prototypes, protection of intellectual property, financial modeling, etc., none of which are necessarily part of the entrepreneur’s skill set. The Kickstarter method is faster, gives much more explicit and quantitative feedback as well as giving direct market research (since backers are also potential customers.)

Table 5. Comparison of the 6 elements for crowdfunding and conventional business for the transition to production stage. Â This is one of the common types of Kickstarter campaigns, used when the entrepreneur runs out of money before finishing development and launching the product. Â The music production and the 3D drawing system examples are at this stage.

| Conventional Business | Crowdfunding | |

| Tool | Entrepreneur | Entrepreneur |

| Object | Funding source | Backers |

| Energy/Engine | Ownership of IP, Ownership of company | Rewards (can be product, or sourvenirs) |

| Transmission | Offer sheet (venture capital terminology) | Kickstarter infrastructure |

| Sensor | Decision by funding source | Number of backers, speed of pledges, amount pledged |

| Control | Modifications to increase desirability of the offer to the funding source | If goal not met, modify the challenge based on the data from the “sensor†|

3. Proposed future work

In the US, changes are pending in the financial regulatory system [12] [16] that will allow crowdfunding ventures to offer equity in the startups as part of JOBS (Jumpstart Our Business Startups.) This will return some aspects of the model to the conventional business model, and it will be interesting to see how that affects the success of the system. When the new regulations are finalized, and the crowdfunding enterprises respond with their methods of using the new regulations, repeating the complete (technical) system model analysis will enable us to see the impact of the changes very quickly.

The analysis presented here has been done from the point of view of the inventor/entrepreneur, and the reduction of the risk to the inventor/entrepreneur caused by the development of the crowdsourced and crowdfunded business models. The development of these new business models may enable the future merging of the roles of “customer†and of “inventor/entrepreneurâ€â€”when all that is necessary to produce something new is to express a desire to have it. The TRIZ concept of ideal final result and the TRIZ patterns of evolution clearly predict the shortening of this pathway.

Conclusion

The TRIZ methodology of identifying the elements of the complete system is useful in the rapidly emerging world of crowdsourcing and crowdfunding in the same way it was useful in its original application. The TRIZ practioner can readily understand the relationship between the 6 elements, can anticipate the evolution of the system, or can improve the overall system.

References

[1] Domb, E., Brewer, T., Application of TRIZ to the New Definition of “Businessâ€, ETRIA TFC 2012.

[2] Mann, D., “Hands-on Systematic Innovation for Business and Management,†IFR Consulting, 2004.  ISBN-13: 978-1898546733. 538 pp.

[3] Zlotin, B., Â Zusman, A., Â Kaplan, L., Visnepolschi, S., Proseanic, V., Malkin, S. TRIZ Beyond Technology: The theory and practice of applying TRIZ to non-technical areas. TRIZ Journal, Jan. 2001.https://the-trizjournal.com/archives/2001/01/f/index.htm

[4] Miller, J., Domb, E. The Importance of Time Dependence in Function Modeling, TRIZ Journal, Dec. 2002.https://the-trizjournal.com/archives/2002/12/a/index.htm

[5] Mann, D.L., ‘Innovation Culture As A System, Systematic Innovation E-Zine, Issue 123, June 2012.

[6] Â Zhuhai-Worrall, M. Finance:Â A field guide to crowdfunding. Inc. Magazine, November 2011.

[7] Terninko, J., Domb, E., Miller, J. Â The Seventy Six Standard Solutions, with examples. TRIZ Journal, Feb. 2000.https://the-trizjournal.com/archives/2000/02/g/article7_02-2000.PDF

[8] Domb, E.,Miller, J. The Complete Technical System and System Operator. TRIZ Journal, August, 2008.https://the-trizjournal.com/archives/2008/08/05/

[9] Domb, E., Miller, J. The Complete Technical System Generates Problem Definitions. Presented at the 2nd Congreso Iberoamericano de Innovacion Tecnologica, Monterrey, N.L. October 30 – November 1, 2007 and at the European TRIZ Association-TRIZ Futures 2007, Frankfurt, Germany, November 6 – 8, 2007.TRIZ Journal, December 2007. https://the-trizjournal.com/archives/2007/12/02/

[10] Brewer, T., Domb, E. Using the ‘patterns of evolution’ to advance crowdsourced designs, ETRIA TFC 2013

[12] Hurst, N. Attack of the Kickstarter Clones:Â Crowdfunding reaches its tipping point.http://www.wired.com/design/2013/05/kickstarter-knockoffs/

[13] http://mashable.com/category/kickstarter/

[14] CNN Business News, Feb. 21, 2013.http://whatsnext.blogs.cnn.com/2013/02/21/a-3-d-pen-that-lets-you-draw-objects-in-the-air/

[15] http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1351910088/3doodler-the-worlds-first-3d-printing-pen?ref=live and http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/bongoloidz/fredo-ortiz-debut-solo-album-bongoloidz/posts/440298?ref=email&show_token=a977079f3d6a9052

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/aug/16/smartphone-fundraising-ubuntu-10m-dollars