The Importance of Innovation Timing: The Fickle Consumer

By Darrell Mann

Undoubtedly one of the most difficult aspects of the innovation challenges is understanding when to launch a new product or service. The challenge is particularly great when dealing with innovations that directly interact with consumers. Critical information can be obtained by digging deeper into the voice of the consumer and market demand.

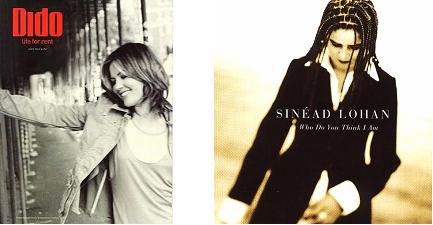

Consider the two singers shown in Figure 1 – one is rather well-known and the other is not.

Many consumers have likely heard of Dido even if they are not interested in Western popular music; she has sold more than 24 million albums, has won a wide range of awards, including a Grammy, and sells out big stadiums when touring. Sinéad Lohan, on the other hand, is relatively unknown to those outside of Ireland. Sinéad sells tens of thousands of albums and tours in small clubs. Listening to both singers swiftly reveals, however, that both have similar singing voices, and use similar phrasing and themes. Musical purists may argue that Sinéad is the more talented of the two. Add to this equation the additional facts that both are about the same age, both released debut albums in 1995 and that both debuts largely disappeared, it seems more than a little unfair that the outcomes are now so different. How can two such similar start points end up with two utterly different outcomes? Could the difference in their success levels be that Sinéad Lohan released her second album in 1998, while Dido’s record company waited until 1999?

This is precisely the sort of question that highlights the enormous difficulties of getting innovation timing right. Apart from dumb luck, what could have led to the conclusion that 1999 was a better year for these two female singer-songwriters to release an album than 1998?

The Question of Innovation Timing

To answer that question means exploring some consumer trend patterns in a fair amount of detail. The best start point for such an analysis is the four-phase generational cycle findings of U.S. historians William Strauss and Neil Howe in The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy.

Figure 2 illustrates a basic grid that can be used to plot consumer phenomena. It plots calendar time vs. age. The diagonal red lines show the approximate generations identified by Strauss and Howe. Individuals born between about 1963 and 1982 are referred to as “Generation X.” For those born at the beginning of this generation (in 1963) the diagonal red line that begins at 1963 on the x-axis shows their life trajectory. Track the line along to the year 2007 and their age reflected is 44.

Using this basic grid, the next job is to begin plotting important cultural events and milestones relative to the topic being researched. In the case of Dido and Sinéad Lohan, this would focus on popular music and important popular music milestones. Milestones are the events that signal some kind of a shift in culture. A classic example would be the work of the Beatles. The Beatles made several culturally significant records, from their debut album in 1963 (the start of “Beatlemania”), to “Revolver” in 1966 (the start of their transition to serious musicians) to “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” in 1967 (the cultural shift that saw popular music transformed into art). These three albums can be plotted onto the year-age grid by, first, mapping their release date, and then the average ages of John Lennon and Paul McCartney (the two creative forces behind the band at the time). See Figure 3.

Both Lennon and McCartney were born in the early 1940s, putting them at the start of the baby boomer generation. The three dots denoting the position of the three albums on the grid match a diagonal line running parallel with the red generation diagonals, showing how the musicians were aging as calendar time passed.

This graph can be used for other influential and popular music milestones by plotting when the albums were released and how old the principal artists involved were at the time, as seen in Figure 4.

What the graphic shows is a series of significant shifts in types of music with, in each case, the release of a particularly important album provoking the shift. The release of the Sex Pistols album in 1977 represents a classic example – a sea-change from bloated, drug-taking, indulgent rock-stars to back-to-the-streets, anyone-can-do-it, safety-pin-through-nose punks. It is likely too early to say whether the release of the Arctic Monkeys debut at the end of 2005 represents another paradigm shift; the fact that it was the fastest selling debut album ever in the U.K., and the band emerged without any record company support or promotion (one of the first bands to benefit from the MySpace phenomenon), indicates that perhaps it does represent a paradigm shift. The patterns observable from the past 50 years seem to support the argument that another paradigm shift was due. Significant shifts take place in the popular music scene about every half-generation.

Extracting Information from the Grid

With this in mind, re-consider the Sinéad versus Dido situation. Figure 4 demonstrates two things about this story:

- The ages they were and releasing their albums in 1998 versus 1999, put the two women on either side of one of the phase shift boundaries. A 1998 album put Sinéad Lohan at the end of one cycle, while the 1999 album put Dido at the start of the next cycle.

- Dido was able to tap directly into that new phase by being featured on Eminem’s breakthrough album; Eminem’s emergence signaled the start of this new phase.

Could It Be That Simple?

Although the argument looks compelling, one case does not make a robust and reproducible method for predicting what will and will not be successful in the future.

There is enough evidence to suggest that there is something important happening in generational cycle shifts. Another example to consider is the phenomenon of author J.K. Rowling and her Harry Potter series. Another cultural paradigm shift that, when plotted onto the grid, begins to demonstrate not only why the books have been so enormously successful, but also why the last in the series is right to be the last.

There are, however, a few differences. The first is that unlike in popular music, where musicians make music for an audience with a similar age, in children’s literature, the author writes for a younger age group. The time between the first Harry Potter book and the seventh lands in the middle of the Generation Y youth market. Secondly, referring back to Strauss and Howe and their description of the characteristics of the different generations, Generation Y is a generation looking for heroes.

Join the Research

Ultimately, as with so many things, the only way to convince all of the people all of the time is to get them plotting their own maps. Innovation planners may be surprised by what they find and may even help discover a vital piece in the innovation timing challenge.

Note: A version of this article was originally published in the May 2007 issue of the Systematic Innovation e-zine.

About the Author:

Darrell Mann is an engineer by background, having spent 15 years working at Rolls-Royce in various long-term R&D related positions, and ultimately becoming responsible for the company’s long-term future engine strategy. He left the company in 1996 to help set up a high technology company before entering a program of systematic innovation and creativity research at the University of Bath. He first started using TRIZ in 1992, and by the time he left Rolls-Royce had generated over a dozen patents and patent applications. In 1998 he started teaching TRIZ and related methods to both technical and business audiences, and to date has given courses to more than 3,000 delegates across a broad spectrum of industries and disciplines. He continues to actively use, teach and research systematic innovation techniques and is author of the best selling book series Hands-On Systematic Innovation. Contact Darrell Mann at darrell.mann (at) systematic-innovation.com or visit http://www.systematic-innovation.com.