Biology – Polka-dot Tree Frog

Kobus Cilliers | On 28, Apr 2019

Darrell Mann

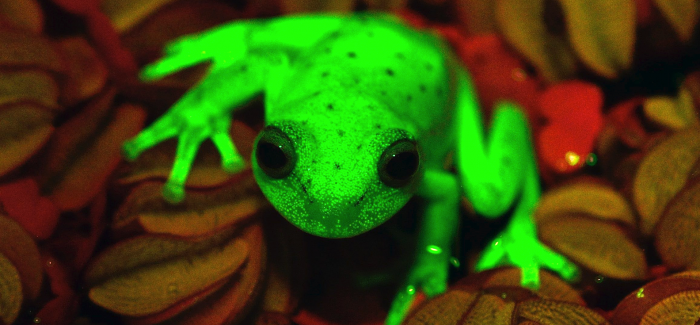

Under normal light, the South American polka dot tree frog (Hypsiboas punctatus) sports a muted palette of greens, yellows and reds. But dim the lights and switch on ultraviolet illumination, and this little amphibian gives off a bright blue and green glow.

The ability to absorb light at short wavelengths and re-emit it at longer wavelengths is called fluorescence and is rare in terrestrial animals. Until now, it was unheard of in amphibians. Researchers also report that the polka dot tree frog uses fluorescent molecules totally unlike those found in other animals.

Because fluorescence requires the absorption of light, it doesn’t happen in total darkness. That makes it distinct from bioluminescence, in which organisms give off their own light generated through chemical reactions. Many ocean creatures fluoresce, including corals, fish, sharks and one species of sea turtle (the hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata).

On land, fluorescence was previously known only in parrots and some scorpions. It is unclear why animals have this ability, although explanations include communication and mate attraction. The associated conflict-to-be-solved, assuming these hypotheses turn out to be true, is the desire to communicate would otherwise be hampered by the amount of energy required to do so. From a Contradiction Matrix perspective, that conflict would map something like this:

Which, all in all, looks pretty good as far as the polka-dot tree frog is concerned, fluorescence being a good example of Principle 28, Mechanics Substitution (i.e. ‘use a field’) in action. Not to mention a touch of Principle 25, Self-Service, thrown in for good measure. Then, zooming in to look at the frog’s fluorescence solution at the micro-scale, how about Principle 3, Local Quality…

…Three molecules — hyloin-L1, hyloin-L2 and hyloin-G1 — in the animals’ lymph tissue, skin and glandular secretions were responsible for the green fluorescence. The molecules contain a ring structure and a chain of hydrocarbons, and are unique among known fluorescent molecules in animals. The closest similar molecules are found in plants, says study co-author Norberto Peporine Lopes, a chemist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil.

The newly described fluorescent molecules emit a surprising amount of light, providing about 18% as much visible light as a full Moon — enough for a related species of frog to see by. Almost nothing is known about the polka dot tree frog’s visual system or photoreceptors, so Taboada plans to study these to determine whether the frogs can see their own fluorescence.

“I think it’s exciting,†says marine biologist David Gruber of Baruch College, part of the City University of New York, who with his colleague discovered fluorescence in hawksbill sea turtles in 2015. “It opens up many more questions than are answered,†he says, including the ecological and behavioural function of fluorescence.

Read more:

- Taboada, C. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701053114 (2017).